Anime Air Plane Flying to Hawaii Easy to Draw

Crossing the Pacific

The U.S. Navy and Army made the first attempts to fly to Hawaii. It was no easy matter. Hawaii lay about 2,400 landless miles from San Francisco–a tiny navigational target in a vast ocean. Few planes could fly that distance without refueling. But Charles Lindbergh's historic transatlantic flight in 1927 made many aviators eager to try.

The Navy's Ordeal at Sea

The Navy decided it would be first to make the 2,400-mile flight from the U.S. mainland to Hawaii, an overwater distance never before attempted. It chose Cmdr. John Rodgers, one of its most respected officers, to lead the flight. Two Navy seaplanes took off on August 31, 1925 from the waters near San Francisco. One soon ran into trouble; then the other's flight took a desperate turn.

"Twenty-one aviators on the Langley concur that the plane has sunk and the search should be discontinued."

Rodgers (center) and crew wave from their PN-9. The Navy stationed ships every 200 miles to guide the flyers, refuel their planes, or rescue them if trouble arose.

Mechanical problems forced one plane down after 300 miles. Rodgers' plane continued on. Some 365 miles from Oahu, while searching for the Navy ship nearby, the PN-9 ran out of gas. The plane's pilot glided down onto a heaving sea.

Nine days after the plane went down, a Navy submarine off Kauai made an astonishing sighting: Rodgers' PN-9 a few miles offshore. The crew had stripped fabric from the lower wing, rigged it between the two wings, and sailed some 400 miles.

The men were starved but healthy. They had run out of food after three days, and water after six. A rainstorm had saved them from dehydration. The crew later received a hero's welcome in Honolulu.

To learn more about the flight of John Rodgers and his crew, visit the Time and Navigation gallery. This model of their PN-9 seaplane is one of the objects in the gallery.

The Army Takes on the Challenge

After the Navy, the U.S. Army Air Corps made the next attempt to reach Hawaii by air. The Army spent years in planning. It developed flight instruments and navigation techniques, made test flights, and set up radio beacons at San Francisco and on Maui to help guide the flyers. For the flight, it chose a Fokker C-2. The tri-motor plane could carry plenty of fuel, but it lacked floats, so it could not alight on water if something went wrong.

"We certainly never expected to encounter frost in the tropics."

Navigator Lt. Albert Hegenberger (left) helped develop the Army's flight instruments and air navigation methods. Pilot Lt. Lester Maitland was a long-distance flyer and record-setter.

Maitland and Hegenberger took off from Oakland on June 28, 1927, and soon ran into problems. A compass failed. The radio receiver cut in and out and then stopped working. An engine began to cough and spit due to carburetor icing.

Nearly 26 hours after leaving California, the Bird of Paradise finally appeared and swooped down around Wheeler Field. Maitland and Hegenberger had made history: the first flight to Hawaii.

The "newest heroes of the uncharted air lanes" received leis and aloha. The New York Tribune said of their triumph, "The cheering crowds at Honolulu see themselves emerging from the lonely isolation of the mid-Pacific."

Coming in on Fumes and a Prayer

Ernest Smith dreamt of becoming the "Lindbergh of the Pacific." But after the Army's Maitland and Hegenberger reached Hawaii before him, he settled on becoming the first civilian to do so. Smith and navigator Emory Bronte took off from Oakland, California, in a single-engine Travelair on July 14, 1927. Aside from radio earphone problems, their 25-hour trip went well – until they began to run low on fuel hours from land.

"Boy, doesn't that dust feel good in your eyes!"

Ernest Smith (left) and Emory Bronte set out to become the first civilians to fly to Hawaii.

Smith and Bronte managed to reach Molokai before their engine finally sputtered to a stop. Seeing no good place to land, Smith skillfully glided their plane down onto a clump of thorny kiawe trees, amid "startled mynah birds and a terrified flock of quail."

Field hands from a nearby ranch came to the aid of the unhurt flyers. They drove them in an old truck down a dusty road to a radio station, where Smith and Bronte sent word of their arrival.

Smith signals their triumph after Army fliers retrieved him and Bronte and flew them the rest of the way to Wheeler Field on Oahu.

This detail from Bronte's navigation chart shows their route and the exact site of their crash-landing.

The Pacific Air Race Disaster

Just days after Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic triumph, the Honolulu Star Bulletin announced a new challenge. Hawaii's "Pineapple King" James Dole was offering $25,000 (over $340,000 today) to the first person or crew to fly nonstop from North America to Honolulu, and $10,000 to the second.

But before the race even got off the ground, the Army's Maitland and Hegenberger and then civilians Smith and Bronte became the first to reach Hawaii by air. So with that glory claimed, the Dole Derby, as it became known, evolved into a one-time race for cash.

"There are but two goals. The Hawaiian Islands or the bottom of the Pacific Ocean."

The race attracted stunt flyers, barnstormers, and World War I pilots hoping to strike it rich. Most lacked the experience (or sense) to fully realize the perils they faced. Many of their aircraft were unsuitable, ill equipped, or badly overloaded.

The race started at noon on August 16, 1927, as the planes took off one by one from a new airfield in Oakland. Even before the starting flag waved, trouble and tragedy had begun.

The Terrible Toll

The race cost a dozen lives. Ten participants died before, during, and after the race. The victims included 22-year-old Mildred Doran, the darling of the event and one of those lost at sea. Two Army aviators died in a crash while searching for the missing planes. The nation was horrified.

Dole had hoped the race would help develop air travel to Hawaii. Instead it reminded people how dangerous it still was to try to reach the islands by air.

"Such an orgy of reckless sacrifice must never be permitted again in this country"

What Happened to the Participants?

Maj. Livingston G. Irving: pilot and navigator

Breese Pabco Pacific Flyer

Failed to take off on the first try and then had to repair a broken tail skid. Crashed during the second try. Survived but dropped out of the race.

Benny Grifflin: pilot

Al Henley: navigator

Travel Air 5000 Oklahoma

First to take off successfully, but returned with a smoking engine. Dropped out of the race.

Lt. Norman A. Goddard: pilot

Lt. Kenneth C. Hawkins: navigator

Goddard Sport Plane El Encanto

Crashed while trying to take off. Survived but dropped out of the race.

Capt. William P. Erwin: pilot

Alvin H. Eichwoldt: navigator

Swallow Dallas Spirit

Took off successfully, but returned with sections of fuselage fabric peeling away. Dropped out of the race. Took off again for Hawaii on August 19 to help search for the missing planes. Crashed into the ocean less than seven hours later. Both killed.

John W. Frost: pilot

Gordon Scott: navigator

Lockheed Vega Golden Eagle

Took off successfully, but never reached Hawaii. Lost at sea.

John A. Pedlar: pilot

Lt. Vilas R. Knope: navigator

Mildred Doran: passenger, and only woman in race

Buehl CA-5 Air Sedan Miss Doran

Took off successfully, but returned with a malfunctioning engine. Took off a second time after repairs, but never reached Hawaii. Lost at sea.

Martin Jensen: pilot, and the only entrant from Hawaii

Paul Schluter: navigator

Breese Aloha

Reached Hawaii after a harrowing flight, during which the plane nearly crashed several times and was blown badly off course. Landed at Wheeler Field two hours after the winner, with only 20 to 30 minutes of fuel left. Won the $10,000 second-place prize.

Arthur Goebel: pilot, and the only entrant from Hawaii

Lt. William V. Davis, Jr.: navigator

Travel Air 5000 Woolaroc

Well equipped with navigational instruments and both a radio transmitter and receiver. Reached Hawaii with little trouble. Landed at Wheeler Field 26 hours and 18 minutes after leaving Oakland. Won the $25,000 first-place prize.

First Transpacific Flight

On May 31, 1928, Australian Charles Kingsford-Smith and three crewmates left Oakland in the single-engine Fokker Trimotor Southern Cross to attempt the longest transoceanic journey by air yet attempted: from California to Australia.

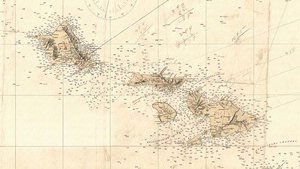

Kingsford-Smith used this navigation chart on his flight from California to Hawaii.

Kingsford-Smtih's Southern Cross first landed in Hawaii. Then the crew set off on an even longer overwater flight: 3,200 miles to Fiji.

Severe storms and high winds battered them beyond Hawaii. When they finally reached Australia after a perilous final leg, they were 110 miles off course.

Charles Kingsford-Smith and his crew of three made the first transpacific flight from California to Australia in 1928 in this airplane. He also made the first transpacific flight in the opposite direction in another plane in 1934. Kingsford-Smith and his copilot vanished over the waters off Burma in 1935 while trying to break the flying record from England to Australia.

Charles Kingsford-Smith wore this fur-lined leather helmet during the first transpacific flight from California to Australia in 1928. His name is written in ink on the right side.

Emory Bronte wore this helmet on his flight to Hawaii with Ernest Smith in 1927.

Source: https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/hawaii-by-air/online/early-flights/crossing-the-pacific.cfm

0 Response to "Anime Air Plane Flying to Hawaii Easy to Draw"

Enregistrer un commentaire